Psalm 133:1 Hineh ma tov umanain Shevet achim gam yachad

“How good and how pleasant it is when brothers all dwell together as one!”

In this series of posts I am reflecting on the life, and death, of my sister, Jenny. Her funeral was on Wednesday, September 9, 2020. Many people, mostly family, attended virtually. In a normal world, I think many of us would have been there in person. But, we are not living in a “normal” world. I have mixed feelings about the whole “virtual” thing. On the one hand it was so nice to see so many of us gathered together. On the other hand it accentuated the distance that lies between us.

The necessity of the new virtual environment pushed onto us by Covid-19 has both separated us and brought us together in ways that we might not have considered even a few months ago. As a teacher, the dynamic of engaging other human beings through an electronic window is an odd one, to say the least. We adapt to a new reality and try to make it work. Sometimes I feel like I am

“tap tap tappin’ on the glass.

I’m waving through a window

I try to speak but nobody can hear

And so I wait around for an answer to appear…”

That experience has more to do with my sister Jenny’s everyday experience than one might think.

Jenny lived most of her life homeless. The reasons for homelessness are plethora; there is not one common denominator that links all homeless people together. No matter what the reason for their homelessness is there are two things that unite the Homeless together: being homeless and being invisible. The Homeless make us uncomfortable. We see them, but we avoid them. We avoid eye contact. If we give them eye contact then we have to acknowledge their existence and then we have to recognize their humanity. And then we feel guilt. If we give them any thought at all, it’s usually to justify our indifference and steel us against empathy, which dehumanizes them even further.

Here is a version of the song “You Will Be Found” from the Broadway musical, “Dear Even Hansen” done in a style that reflects our digital separation during these Covid times. It makes it even more poignant, I think. Part of the beauty of the song is that, if you take the song out of the context of the pay that it comes from, the lyrics evoke emotions that are universal. In this case, it connects me emotionally to Jenny’s homelessness, and by extension all those who are homeless: Those who feel like there is no one there; those who feel forgotten. . .

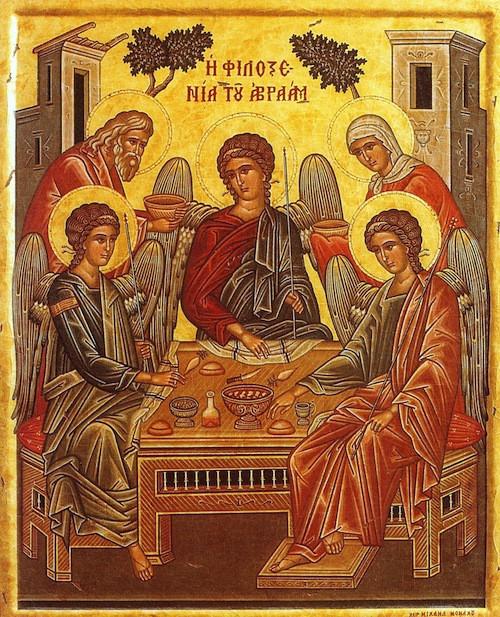

Ovid tells the story of Zeus and Hermes disguising themselves as homeless people, wandering the town looking for hospitality of any kind, but none was to be found. People walked by. No one gave them eye contact. And some people even scorned them. The hospitality they found was not with the people who could afford it, but the poorest of the residents, Baucis and Philemon.

How many of the gods have we walked past? How many have we ignored?

Good mythology is designed to help us to navigate the difficult terrain of life. It not only helps us to navigate our relationships with the gods, but even more importantly how we navigate our relationships with each other. In the above scenario the town was judged, and harshly, for how it treated its (seemingly) weakest members. The town was destroyed by flood, the only people saved were Baucis and his wife Philemon, who recognizing their humanity came to recognize their divinity.

Stories like this abound in myth, and they all play out the same. In the Tanakh (what Christians would call the Old Testament) the parallel story is the story of the destruction of the cities of “Sodom and Gomorrah.” In that story the divine beings disguised as homeless people (some translations say “angels” and although that is not a bad translation, it can also be translated as “divine beings.”) look for hospitality and compassion in the town and do not find it, except in the house of Lot and his wife. Those towns are destroyed by fire. (The method of destruction is consistent with the geographic location of the story’s origin.)

Certainly, a society can be judged by how it treats its most vulnerable members.

People are so eager to disassociate themselves from any personal responsibility that we have, traditionally, gone out of our way to make the story of “the Destruction of Cities of Sodom and Gomorrah” into something that it is not. But the prophets do not let us forget. The real questions raised by the story are indeed damning, but we are blinded to the meaning because the traditional interpretation is such an alluring red herring that our attention is completely diverted from the thing that we are suppose to see. The real questions raised by the story are:

Why are there homeless people?

Why are there hungry people?

Why are there children without parents?

Why is there social inequity?Why is there such a gap between the rich and poor?

Often we look at large social problems and calm our conscious by saying things like:

There is nothing I can do about it.

It’s not my problem.

Or sometimes we shift the blame onto the other person.

But the prophets are there to remind us of the meaning behind that specific story.

The Prophet Isaiah (IS 1: 10 – 23)

10 Hear the word of the Lord,

princes of Sodom!

Listen to the instruction of our God,

people of Gomorrah!

11 What do I care for the multitude of your sacrifices?

says the Lord. . . .

Your hands are full of blood!

16 Wash yourselves clean!

Put away your misdeeds from before my eyes;

cease doing evil;

17 learn to do good.

Make justice your aim: redress the wronged,

hear the orphan’s plea, defend the widow.

18 Come now, let us set things right,

says the Lord . . .

21 How she has become a prostitute,

the faithful city, so upright!

Justice used to lodge within her,

but now, murderers.

22 Your silver is turned to dross,

your wine is mixed with water.

23 Your princes are rebels

and comrades of thieves;

Each one of them loves a bribe

and looks for gifts.

The fatherless they do not defend,

the widow’s plea does not reach them.

The Prophet Ezekiel (EZ 16:49-51)

49 Now look at the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters were proud, sated with food, complacent in prosperity. They did not give any help to the poor and needy. 50 Instead, they became arrogant and committed abominations before me; then, as you have seen, I removed them. 51 Samaria did not commit half the sins you did. You have done more abominable things than they did. You even made your sisters look righteous, with all the abominations you have done.

The Prophet Jeremiah (Jer 23:14)

Adultery, walking in deception,[a]

strengthening the power of the wicked,

so that no one turns from evil;

To me they are all like Sodom,

its inhabitants like Gomorrah.

Jesus

In both the Gospel of Matthew (MT 10: 11-15) and the Gospel of Luke (LK 10: 1 – 12) Jesus references the cities in their lack of care for those who need it most. In other words, he agrees with the prophets.

So, maybe if we think that the story means something other than Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah and Jesus, maybe, just maybe, we are wrong. Maybe what we should be concerning ourselves with is eliminating the disparity between the rich and poor, living justly, and taking care of the most vulnerable around us.

Here is the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 25, verses 35-45 (MT 25:35-45). Although he does not explicitly reference the story from Genesis, he does clearly echo the prophets:

35 For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me,

36 naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me.’

37 Then the righteous will answer him and say, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink?

38 When did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you?

39 When did we see you ill or in prison, and visit you?’

40 And the king will say to them in reply, ‘Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.’

41 Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you accursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.

42 For I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me no drink,

43 a stranger and you gave me no welcome, naked and you gave me no clothing, ill and in prison, and you did not care for me.’

44 Then they will answer and say, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or ill or in prison, and not minister to your needs?’

45 He will answer them, ‘Amen, I say to you, what you did not do for one of these least ones, you did not do for me.’

So, according to Jesus and the Prophets, it IS our fault.

No one can single-handedly end homelessness. But that’s just it: it’s not about you. It should never be about you. It is about us, together.

The day after Jenny’s funeral, as I was thinking about all this, I just happened upon the story of this amazing young man, who was homeless for a year and a half and now – amazingly – is a student at Boston College. After he was accepted to BC he walked from VA to MA to raise awareness of homelessness. Here is his story.

People like Gordon give me hope.

I’ll close out on a note of hope. The words that I opened with are from Psalm 133 and celebrates what the world could be like if we were to recognize each other, and take care of each other.

Here are those words put to music in one of the most well known songs in Judaism. In this video, everyone is separated due to the pandemic – which, in itself is a metaphor for the many ways that we are separated from each other – but sing out joyfully as one:

Psalm 133:1 Hineh ma tov umanain Shevet achim gam yachad

“How good and how pleasant it is when we all dwell together as one!”

(I love this version! I love that there is so much diversity represented among the participants: men and women, old and young, big and small. . . .)

The next time you pass someone who appears homeless, say hello. Look them in the eyes and acknowledge their humanity; maybe you will even recognize their divinity.