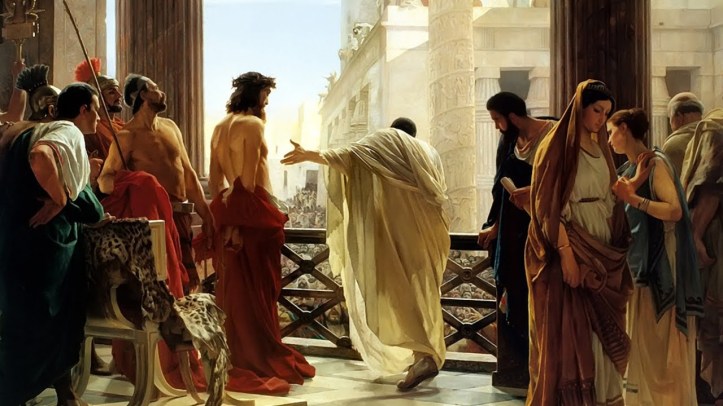

Ecce Homo by Antonio Ciseri

In one way or another, religion has been a part of my entire life; and Religious Studies has been a part of my entire academic and professional life. All religions (ALL religions) want the future to be better than the present. It is also true that people within religions have differing points of view as to how that better future will be come about. Some people believe that it is through righteous violence that this will be achieved. Some believe that it is though peace. It is hard to see how these points of view could be reconciled. I don’t think that they can be.

Although most of us think of this religious polarization in a modern context, it is not new. As we move through Holy Week, I am reminded of a scene written in the Gospel of Mark in which Jesus is tried against a man named Barabbas. (MK 15:6-15). It must have been a popular story. Not only do the authors of Matthew and Luke copy the story (which is the normal relationship among the synoptic gospels), but the author of John mentions it, too. (This must have been a story passed on orally, since there is no evidence of John copying Mark, like Matthew and Luke do, suggesting its popularity in the minds of the early Christian communities.)

There are many reasons to suggest that this is story is ahistorical. First, Pilate offers the crowd the choice of releasing one of two prisoners in accordance with a Passover tradition (MK 15:6.) There was never such a tradition. In fact, the people at the end of the first century (who were the intended audience) would have known this, thus identifying it in the context of the greater narrative as ahistorical (not historical). So, if not historical, then the importance must lie in interpretation. That is, it lies in the way that the first century audience would have heard it.

Second, the thought of Pilate entertaining a trial at all is a little hard (although, not impossible) to believe. He was known to accept bribes, carry out underhanded dealings, and have a penchant for executions without trials, all of which (most notably the latter) resulted in his removal from office by the Roman government in 36 CE. Lastly, an open and participatory Roman trial by a crowd of people like the one described is completely unattested. These things all draw the historicity of the event into serious question.

But still the story made its way into the popular imagination and was perpetuated to the extent that other authors, who did not use the same sources, knew the story and related it in their writings. Perhaps, as is often the case, there is more to the story than meets the eye in a first reading. Part of its popularity was undoubtedly part of a rising anti-Semitic sentiment that was becoming normalized both in government and among the new Christian cult. In John’s retelling of the story, the crowd is specifically referred to as “the Jews” thus making it clear that “the Jews” were responsible for the death of Jesus, and not the Romans, despite the fact that crucifixion was a form of execution used by Rome – and not by the Jewish community. (The further exploration of the unfortunate anti-Jewish polemic in the gospels should be the topic of another article.) But that only helps us a little. The use of the crowd as an anti-Jewish polemic is unfortunate, but the crux (sorry, I couldn’t help myself) of this short narrative is something else (although, not totally unrelated.)

In 64 CE, just a few years before Mark was written, the Christian community in Rome was scapegoated for the great Roman fire that swept through the city destroying homes and businesses, killing many who could not escape and dislocating even more into homelessness. Even though the fire was most probably caused by an order from Nero, the new Christian cult was an easy scapegoat. No one really understood them. Their founder was Jewish, and they claimed to be monotheistic, but they were not Jews. They had rituals in people’s homes in which it was rumored that they ate human flesh and drank blood. They were known to commit to the cult wholeheartedly, giving all of their possessions to the group in order to “hold all things in common” and trusted the elder to “divide them among all according to each one’s need.” (Acts 2:44-45, 4:32)

Hate crimes against Christians rose dramatically, even to the point of being sanctioned by the state.

It was during this time that the author of the Gospel of Mark moved to Rome from Palestine after he, himself, was displaced by another kind of violence.

In the year 66, tensions between Rome and the Jews in Palestine had escalated into a series insurrections largely instigated by apocalyptic Jewish sects, including Zealots and the Sicarii (literally, “the Daggers”), who saw violence as the only option. It resulted in a long, drawn out war that lasted until 70 CE (73-74 CE if you use the siege of Masada as the end of the war.) It was by all accounts, a truly horrible time to be a Jew in Palestine. It was during this time that an apocalyptic Jew, who was a follower of the Jesus movement, moved to Rome where he would write his gospel for the Christian community there. (The Gospel of Mark) He was a refugee of the horrible destructive violence that swept through Palestine. It is not a stretch to imagine the pain and the loss that the author must have experienced, culminating in the loss of what was the most important symbol of a unified Judaism; the Temple. (This also helps us to understand why the Gospel of Mark is so emotional and tends to focus on Jesus’ humanity and suffering more than any other canonical gospel. The author’s own sense of grief and loss come through on the pages with a visceral poignancy.)

Now we come to the famous story of the trial.

The earliest version of the story comes in the Gospel of Mark (Which was the first of the canonicals to have been written) and can be found in MK 15:6-15. (I’ll leave it up to you to read the translation of your choice.) In the story, Jesus is juxtaposed with a man named Barabbas. We find out that Barabbas was “in prison with the rebels who had committed murder during the insurrection.” We are never told what the insurrection was, but the first century audience wouldn’t have needed that particular clarification.

Most Palestinian Jews in the first century were apocalyptic and expecting a messiah (Hebrew: mashiach, equivalent to the Greek: Christ). The apocalyptic solution was a popular one; the idea that God would act to change the balance of power to recreate the world as a world of peace. Most people thought that the only way to achieve this was through an ultimate battle. This battle would either start or culminate on the field of Megiddo. The field being designated as Har, in the same way that the hill on which the city sat was a Tel. (Think, “Tel Aviv.) So, the final battle had an important connection with Har Megiddo – which is why the battle itself would be called, HarMegiddon (phonetically: Armageddon). This ultimate act of violence was approached in two ways. In one interpretation, the people should act, to show God that they were ready for the war, and then God would oblige by starting the apocalypse. This was a view shared by people like the Zealots and the Sicarii, and so were known for acts of murder and terrorism. The other point of view was not to fight until the Messiah started the war. Until then they would simple wait and prepare. There is a third point of view, which was Jesus’. Jesus did not see a battle at all. Jesus was an absolute pacifist, and made that a requirement to be among his followers. The apocalyptic event would come, but God had that in hand. All we needed to do was to be ready.

So, on the one hand we are presented with Jesus the pacifist. On the other hand we are presented with Barabbas the insurrectionist. What makes it even more poignant is that Barabbas means “Son of the Father,” and he is being juxtaposed with Jesus, “The Son of the Father.” The word-play in undeniable. And then the author of Mark does what the author of Mark is good at: he breaks the fourth wall, as it were, and turns to you, the reader, and asks you to make a choice. The crowd is a device meant to represent you. We are faced with the choice of choosing Peace or Violence. Mark thinks that we are a predicable lot. When faced with solving our problems peacefully or with violence, we most often chose violence. (Look at national budgets to see where the money is allocated to verify that claim.)

And so, in the story, we do. We do choose violence over peace. And, it is not enough to choose that violence be among us, but we must violently rid ourselves of the peaceful option.

So, Barabbas, the Son of the Father of Violence is among us. We turn our back (or worse) to Jesus, the Son of the Father, God who is with us (Emmanuel = God with us.)

Whether we are a believer or not. The story of Jesus and Barabbas is an example of genius story telling that is just as poignant now, as it was in 70 CE.

Which do you choose to put your faith in?